Summary and takeaway

This experiment explores how formatting impacts the support for or opposition to policy bans. The results confirmed our hypothesis that in the default matrix format participants are often faced with, they are not perceiving the word “ban” in the question stem, leading to an inaccurate measure of support for the bans across party IDs. Most surprisingly, bolding and underlining the word “ban” in the question stem did not reach a threshold to grab respondents' attention. Only when “ban” was moved to the item level of the matrix did results align in the ideologically expected direction. These results highlight that we, as researchers, collect better data when we ease the cognitive burden and meet participants where they are - at the item level.

Introduction and background

In an ideal world, survey respondents would be actively engaged with each and every question they are asked. However, participants can sometimes default to autopilot and answer the question they expect to be asked. Matrix-style questions - where the question stem is separated from the items - may be even more susceptible to this type of cognitive trap, especially when important question context is located in the stem. This Methodology Matters experiment demonstrates the importance of question formatting in accurate measurement in surveys.

Attention in survey research is traditionally measured through attention checks asked at one point in time and the results are often generalized to an attentiveness measure for the entire survey. Rather than a binary measure, attention can be considered a limited resource. Daniel Kanheman (2011) described human thinking and decision making as operating as two systems. System 1 is the default state, where little conscientious effort is exerted, while system 2 is a limited resource of cognitive effort. Unless otherwise necessary, most people will continue to operate in system 1, reserving system 2 for more complex tasks (Kanheman, 2011). In the default state people tend to rely on biases and heuristics to respond quickly, which can lead to incorrect responses. Getting people to engage in that extra processing step can prove difficult, and expecting respondents to remain at maximum attentiveness throughout a survey is unrealistic.

Because respondents are relying on heuristics and quick processing to answer, researchers should actively design surveys with this in mind. While matrix grids can be a useful tool to save participant time and effort when asking about a group of items along the same response scale, the design may exacerbate these traps. When asking participants to evaluate compound questions - such as how they feel about different policy bans - relegating key instructions to the stem may lead to misrepresentation of participants’ attitudes.

Take, for example, a matrix that asks respondents “Do you support or oppose a ban on…” with “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Initiatives” at the item level. Participants are required to do extra processing to connect “DEI Initiatives” back to the stem. A participant responding to this question without engaging in extra processing can fall victim to defaulting to how they feel about the issue (ex - support DEI initiatives), rather than how they feel about the ban (ex - oppose a DEI initiative ban). Additionally, this default response may be further compounded by the hot-button nature of many topics. Respondents can have strong pre-established opinions on divisive issues in the news (e.g. abortion, DEI, etc.), and may respond quickly to these keywords - ignoring important question context atop the matrix. If researchers aren’t careful they can end up drawing incorrect conclusions from bad data. However, can careful question design be used to overcome these traps and ease the cognitive load on participants?

View data collection methodology statement

Experimental setup

To evaluate the impact of question formatting on support for bans, we fielded a survey experiment. A matrix-style question consisting of five proposed bans previously covered in the news was formatted in accordance with 3 conditions: no formatting (control), bolding, and in-line condition. Respondents were randomized to one of the three conditions.

Within the grid, we asked about bans on TikTok, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives, transgender athletes in college sports, dynamic ticket pricing, and Daylight Saving Time. These items were chosen because they represented a mix of politically divisive items (TikTok, DEI, transgender athletes) where we had a general expectation for overall party opinions. Additionally, we included some less politically divisive items (dynamic ticket pricing and Daylight Saving Time) to test the robustness of the formatting conditions on items where we don’t have strong baseline predictions. Additionally, bans for many of these items had recently been in the news and participants would be familiar with the topics. This is especially true for TikTok and DEI initiative bans, which had been enacted (and in the case of TikTok, reversed) shortly before this experiment.

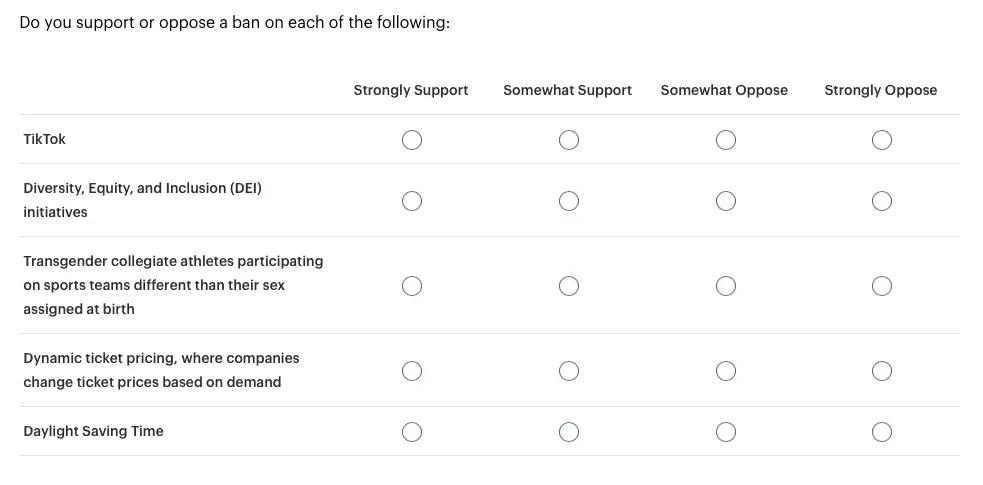

No Formatting (Control)

The control condition was set up as a standard matrix and contained the main question with no additional formatting: Do you support or oppose a ban on each of the following.

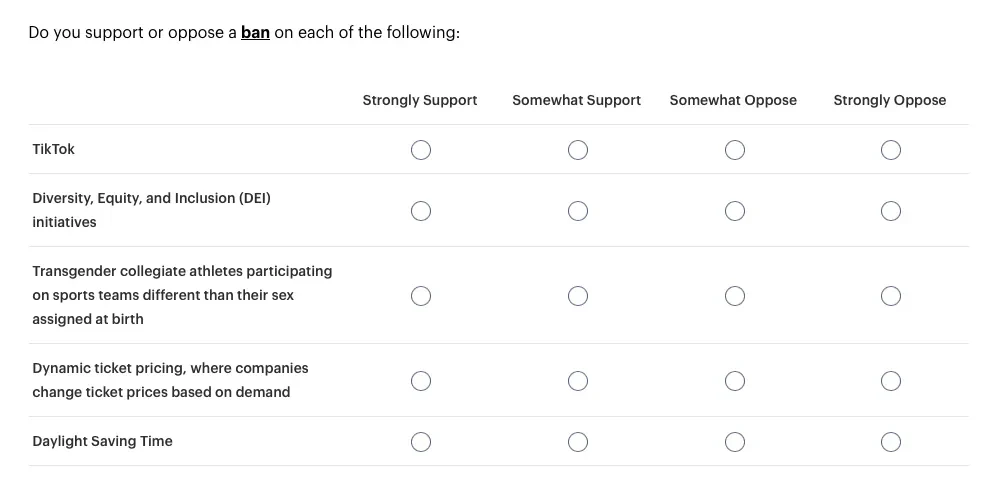

Bold

In the bold condition, the same question display was used. However the word “ban” in the question text was bolded and underlined to give emphasis.

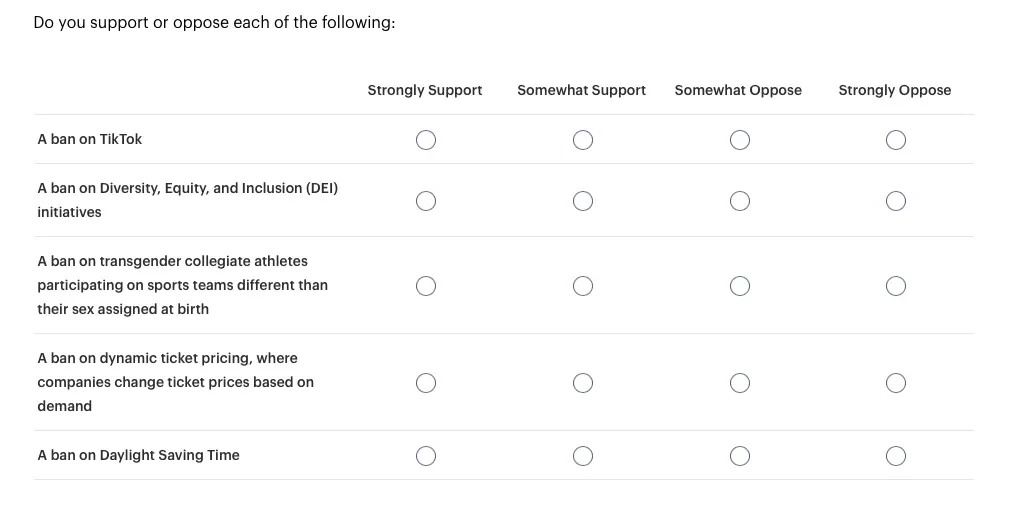

In-line

In the in-line condition, the word “ban” was moved from the question text to before each grid item.

Research Hypotheses

Our main goal with this experiment was to answer the question: To what extent does the formatting of questions impact the support for or opposition to a ban on different policies?

Prior to fielding we hypothesized the following:

- Hypothesis 1: The more apparent the word “ban”, the more strongly the responses will align with expected party views.

- Hypothesis 1a: When “ban” is emphasized through formatting (bolded/underlined) in the question stem, there is greater polarization between support and opposition compared to no formatting (control).

- Hypothesis 1b: When “ban” is placed at the item level, there is greater polarization than when “ban” is in the stem alone.

- Hypothesis 1c: There will be stronger polarization in the partisan items compared to nonpartisan topics.

Methodology

In order to evaluate our hypotheses, we surveyed 2,452 participants from February 27th to March 5th, 2025. The 4-point likert scale was collapsed into binary “support” or “oppose”. As part of the survey, participants were asked their party ID among other demographics. A binary logistic regression was conducted for each of the items to examine whether formatting treatment, party ID, and the interaction of treatment and party ID significantly predicted support for or opposition to the ban. For party ID, we used 7-point party ID recoded to 3 points to include Independents who lean towards one party.

Results

We find evidence in support of our main hypothesis and 2 of the sub-hypotheses:

- Hypothesis 1: We saw significant changes in the amount of support for the bans by party for the in-line condition for all five topics, providing support for hypothesis 1.

- Hypothesis 1a: Contrary to hypothesis 1a, we did not see any significant effect of bolding on the level of support for any of the five topics.

- Hypothesis 1b: The in-line treatment was significant for 4 of the 5 topics, and the interaction was significant for all 5 topics.

- Hypothesis 1c: There were stronger differences in the politically divisive items compared to the non-political items.

To best explain the results, we will break down the outcomes by topic.

Our baseline expectation was that Democrats largely support DEI initiatives and would therefore oppose a ban on these initiatives. Likewise, we expected Republicans to largely oppose DEI initiatives and therefore be in support of a ban on these initiatives. We did not have any predictions about Independents.

In the no formatting condition, we observed the exact opposite of these expectations. The majority of Democrats (60%) reported supporting the ban, while only 39% of Republicans supported it. This party effect was significant in the model (p<.001). Most importantly, there were significant effects for both treatment (p<.001) and the interaction of party ID and treatment (p<.001). Eighty-six percent of Democrats reported opposing the ban, compared to only 40% and 44% in the no formatting and bold conditions respectively. Conversely, support for the ban among Republicans in the in-line condition was 78%, up significantly compared to the 39% and 44% in the no formatting and bold conditions.

For Independents, we do not see a dramatic shift in support opinions across the formatting conditions. This is not entirely surprising and may be indicative of mixed opinions on DEI initiatives masking any impact of formatting.The interaction of party ID and treatment was significant (p<.001) for Independents in the in-line condition, providing further support for this idea.

We did not find evidence to support hypothesis 1a, as we did not see significant differences in responses in the bolding condition or the interaction of bolding and party ID.

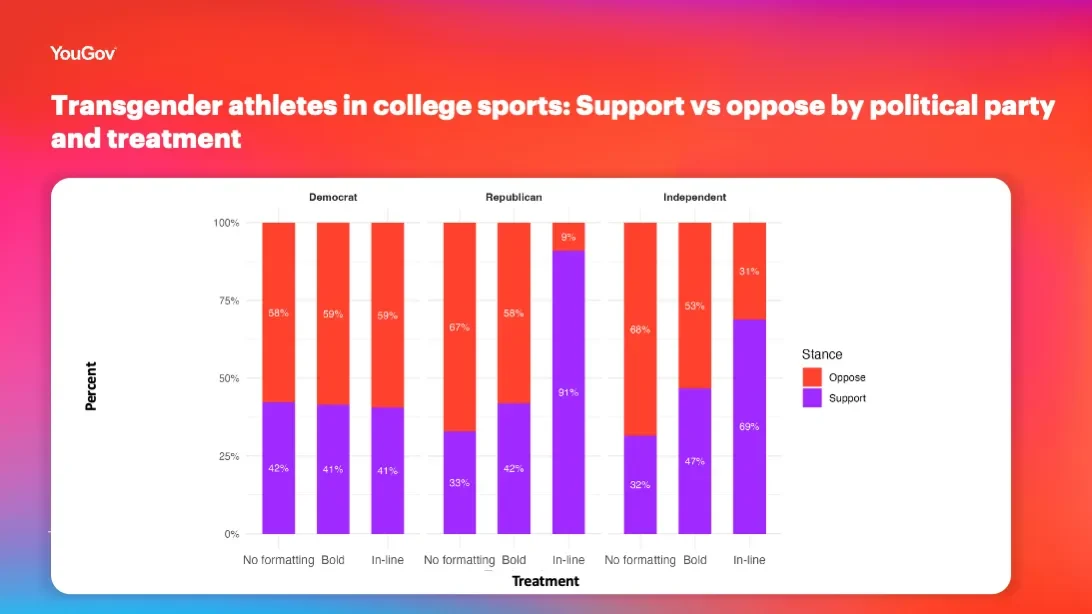

Transgender athletes participating in college sports is another item we expected to be divisive along party lines. Surprisingly, Democrats had more mixed reactions to this item than we anticipated. Because of this, the interaction between treatment and party was only marginally significant for Democrats (p=.053).

We did, however, observe significant interactions in the in-line condition for Republicans and Independents (p<.001). Ninety-one percent of Republicans in the in-line condition reported supporting the ban, compared to only 33% and 42% in the no formatting and bold conditions. Similarly, 69% of in-line Independents supported the ban, compared to 32% and 47% in the no formatting and bold conditions.

Like the DEI item, we did not observe support for hypothesis 1a. There was no significant effect for bolding across the parties.

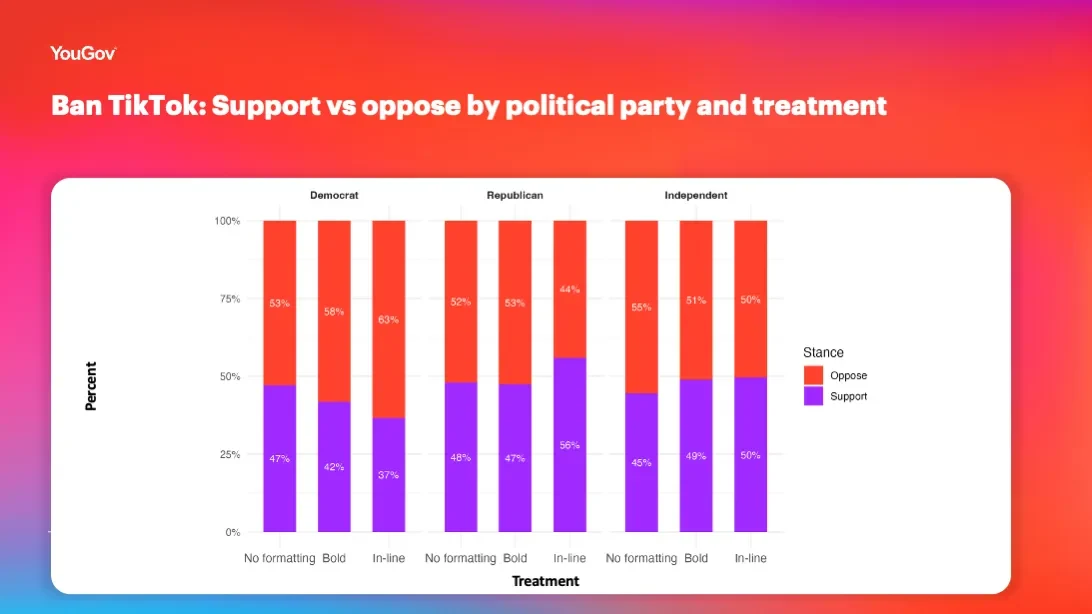

We initially expected the ban on TikTok to be one of our politically divisive topics. While the differences are much less pronounced than the previous two items, we did observe significant effects for treatment and the interaction of treatment and party. For Democrats, in-line formatting significantly decreased support for the TikTok ban (p=.01), going from 47% in the no formatting condition to 37% in the in-line format. Conversely, Republicans and Independents saw increased support for the ban in the in-line condition. The majority of in-line treated Republicans (56%) supported banning TikTok compared to only 48% and 47% in the no formatting and bold conditions.

Independents once again had a more mixed reaction to banning TikTok. Fifty percent of Independents in the in-line condition wanted to ban the app compared to only 45% in the no formatting condition. This interaction between party and treatment was significant (p <.05).

Finally, we did not find evidence in support of hypothesis 1a as there was no significant effect for bolding.

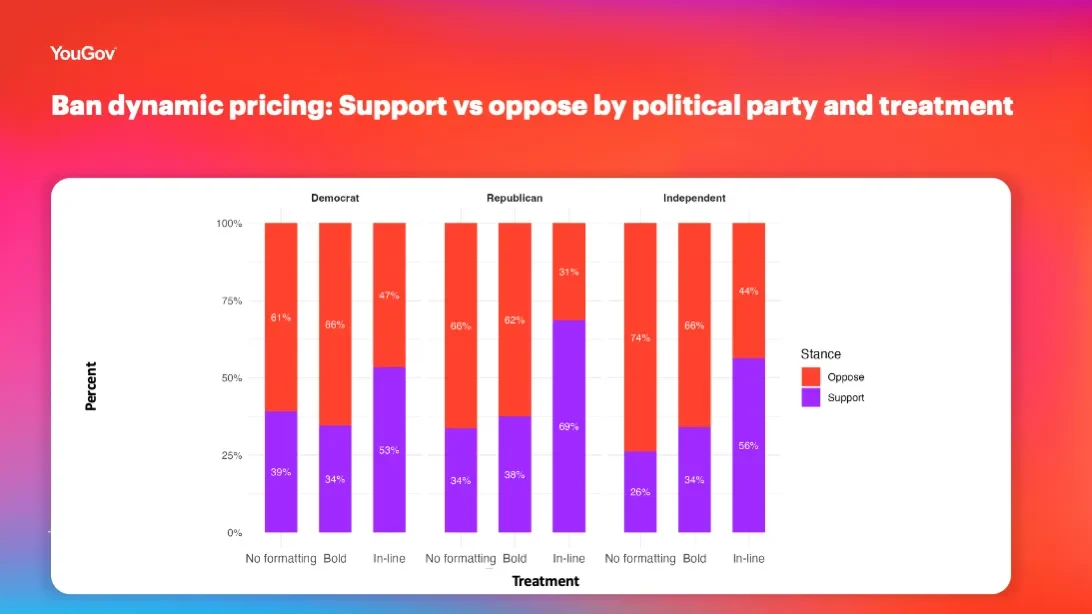

Unlike the previous items, we did not predict strong party division for a ban on dynamically priced tickets. With growing frustrations about rising ticket prices and drastic fluctuations of these prices based on real-time demand, we expected to see similar levels of support for the ban across all three parties. Even though we saw similar levels of support across the parties, formatting still had a significant effect (p<.01) and the magnitude differed across party ID.

For Democrats, the in-line treatment increased support for the ban (p=.001) to 53% compared to only 39% and 34% in the no formatting and bold conditions. For Republicans, we saw a 35% increase in support for the ban compared to the control (p<.01) - 21% larger of an increase than we observed among Democrats. We saw a similar dramatic rise in support for banning dynamic pricing among the Independents (p<.001).

Once again, there was no significant effect for bolding in levels of support.

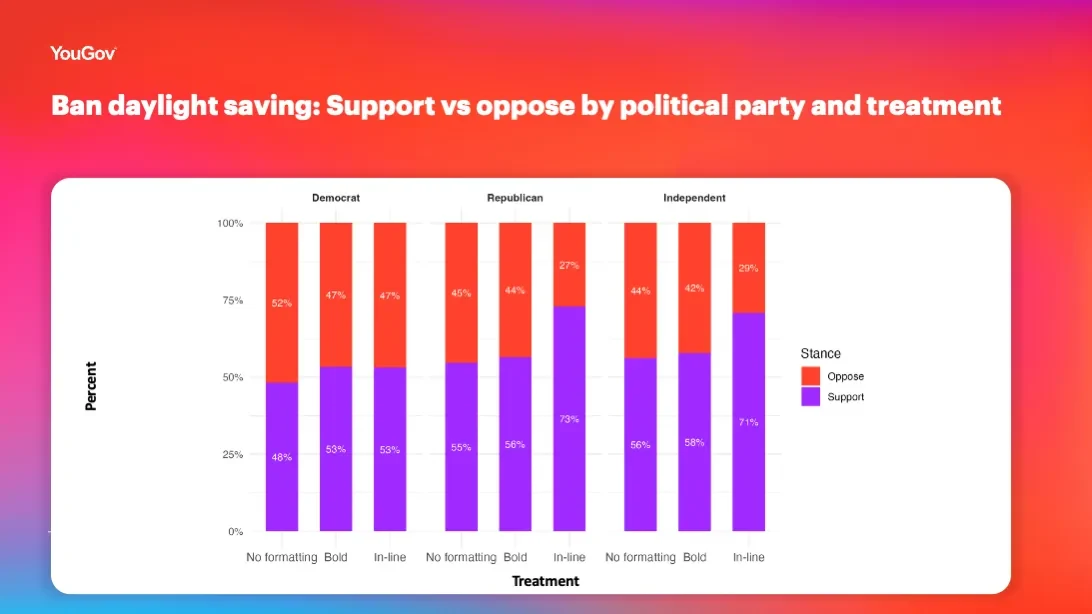

Similar to dynamic pricing, we did not predict significant party differences for banning Daylight Saving Time. However, we observed significant interaction effects for the in-line treatment for Republicans and Independents (p<.05). Republican and Independent support for banning Daylight Saving Time increased to 71% in the in-line treatment.

There were no significant effects for treatment among Democrats. This may be a case where the opinions amongst Democrats are mixed, masking any treatment effects. The movement in opinion among Republicans and Independents suggest that if there is a disconnect between true opinion and first impression, the in-line formatting can reveal that difference.

General discussion

This experiment highlights the importance of careful survey design and its potentially large effects. Across our matrices, we saw significant changes in reported levels of support for or opposition to a ban depending on whether or not “ban” was included at the item level or in the question stem. As researchers, we often design questions with the expectation that participants are reading every word - or are at least paying attention to where we direct them via text formatting. However, our results showed this is not always the case. Contrary to what we expected, bolding and underlining the key word was not enough to capture respondent attention in a way that created significant and meaningful improvement in data accuracy. These results suggest that some participants may not be reading matrix question stems at all. Rather, they are likely relying on the answer scale and the items to get the context they need to answer the question. As researchers, it is imperative that this “item-only” focus is taken into account when designing questions.

In this study, we asked participants whether they support or oppose a ban to mimic some real-world time-relevant questions being used in research. However, supporting or opposing a ban introduces a sort of double negative that can be cognitively difficult for participants to consider. Further research is needed to explore the limitations of the item-level design, such as more straight-forward, less cognitively taxing design. Additionally, this study focused on matrix-style questions, but future research should explore whether other question types may be better suited to accurately measure participants' attitudes when important context needs to be included in the question text.

About the author

Sara Sermarini, Senior Project Manager, Scientific Research, YouGov

Sermarini manages special research projects with experience in conducting psychological, political, and multinational market research studies for both academic and industrial clients. She helps clients meet their research objectives by assisting with the survey design, targeting niche populations, and meeting project deadlines. She collaborates with YouGov's operations and analytics teams as the survey moves from programming to final analysis to ensure high quality participant and data standards are met. Sermarini earned a B.S. in Business Administration from Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania and a M.S. in Behavioral and Decision Sciences from the University of Pennsylvania.

About Methodology matters

Methodology matters is a series of research experiments focused on survey experience and survey measurement. The series aims to contribute to the academic and professional understanding of the online survey experience and promote best practices among researchers. Academic researchers are invited to submit their own research design and hypotheses.